Study Finds Cloth Masks Protect Wearer, Others

Researchers from Virginia Tech recommend well-fitted three-layer masks to help prevent the spread of COVID.

A recent study out of Virginia Tech found that cloth face coverings help to protect both the wearer and others who are nearby from spreading the coronavirus.

The research, led by airborne disease transmission expert Linsey Marr, found that a well-fitted three-layer mask with outer layers made of a flexible, tightly woven fabric and an inner layer designed to filter small particles provides at least 75% filtration efficiency from respiratory droplets produced during breathing and speaking.

Linsey Marr, a civil and environmental engineering professor at Virginia Tech, and students Charbel Harb (left) and Jin Pan (right) worked on a recent study on the effectiveness of cloth masks.

“Some people say, ‘Well, an N95 respirator can block 95% of that most penetrating particle size, and anything else is worthless,’ ” says Marr, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech’s College of Engineering. “It’s true that some of the cloth masks that we looked at only block 10 or 20% at that size. But once you get up to the sizes that we think are more important for transmission, like 1 to 2 microns or even 5 microns, those cloth masks are able to block half or more.”

SAR-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is about 0.1 microns large, but, Marr notes, “it doesn’t come out of us naked.” Instead, it’s carried in larger respiratory droplets, or aerosols, that contain salts, proteins and organic compounds, leading to aerosols up to 100,000 times larger in mass than the virus itself. For their study, Marr’s team focused on a size range of 1 to 2 microns for testing homemade and commercially available face coverings.

“It’s not something I would ask a healthcare worker to wear in high-risk situations,” she says. “They would need the best protection we can get. But given that it’s impractical to have everyone in the general public walking around wearing an N95, I think homemade masks are definitely helpful.”

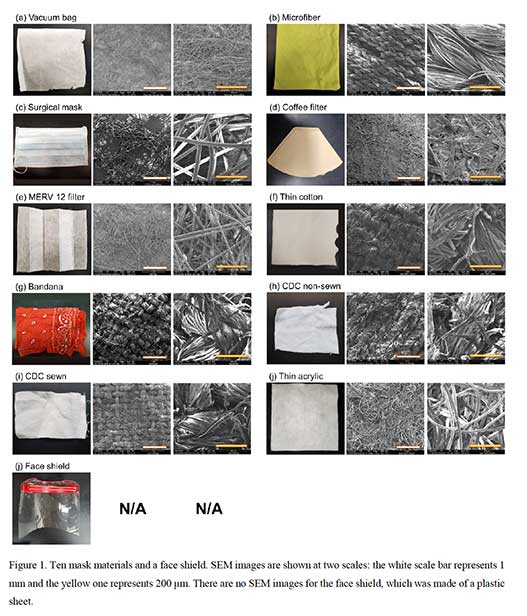

In the study, Marr and her team of researchers set up conditions as close to day-to-day life as possible to best match how people go about a typical day wearing face coverings. They looked at nine homemade masks, as well as a surgical mask and a face shield, evaluating their ability to trap particles in size from 0.04 microns to more than 100 microns. Each mask was tested for outward efficiency – how well it traps particles exhaled by the wearer – and inward efficiency, for mask wearers as they inhale. At the low end of particle sizes, homemade masks performed poorly, but at the larger end, several of the masks could trap 50% to 80% of particles in tests of both inward and outward efficiency. Given what scientists have learned in the last year about how the coronavirus is spread, that performance is significant, Marr says.

Virginia Tech shared electron microscope scans of the material tested in the study. Click here for a larger image.

In the testing, researchers mounted two manikins on opposite sides of a chamber to mimic a pair of inhaling and exhaling people talking closely. They connected the exhaling manikin to a medical nebulizer that generated droplets from the mouth. The other manikin had a vacuum line in the mouth to mimic inhaling. Measurements were taken of particles in the chamber from both sides.

The team found that masks tended to perform better as sources of outward protection than inward, but the differences in most cases weren’t statistically significant.

Because of the controlled setup and lack of human subjects, the research has some limitations, according to Marr. Chiefly, the experiments didn’t factor in things like mask adjusting or variability in airflow that occurs when people breathe in and out. Still, Marr believes her team’s work is a good complement to other studies being done on reducing transmission of the coronavirus.

“No one study by itself is going to tell you the whole story,” Marr says. “And no one intervention will stop the spread of COVID-19 alone. The mask is one of the many interventions that we need to combine together.”

The Virginia Tech study, published in November on medRxiv, has not yet been peer reviewed.